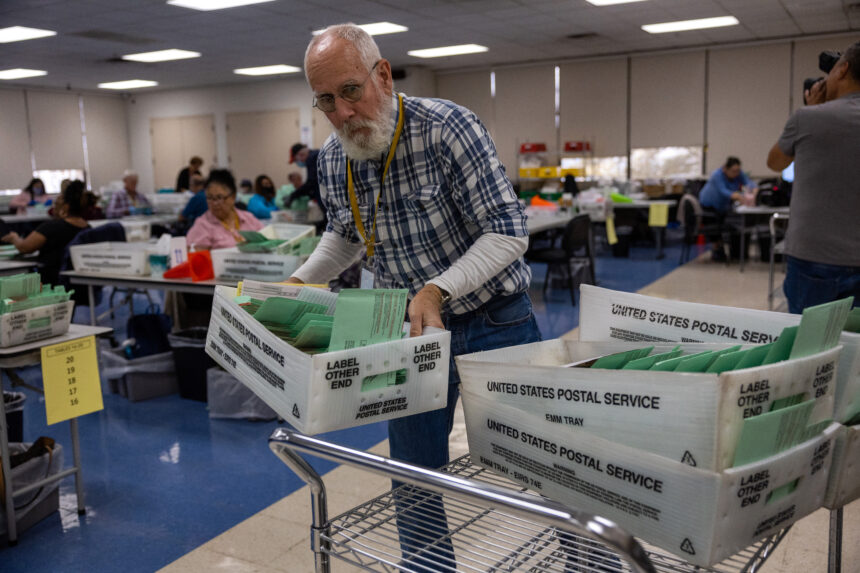

Besides states counting votes faster and starting the process sooner, mail-in voting is expected to be down compared to 2020, when the pandemic led an unprecedented number of voters to avoid polling places in person.

But problems remain. Counting procedures vary from state to state, and partisan infighting has sometimes hampered changes desired by election workers. And some key states — notably Pennsylvania — are still lagging, election officials and experts warn, and in an exceptionally close presidential race, it could still take days to know the winner.

This rush follows the 2020 election. That year, the combination of an increase in mail-in voting, outdated state laws and an election system struggling for resources led to what a race presidential election was not called for several days.

One of the main problems that year was that a handful of swing states did not allow mail-in ballots to be preprocessed before Election Day. The work required to prepare mail-in ballots — validating voter identities, removing ballots from envelopes and loading them into tabulators — takes time. The sooner this is done, the sooner the ballots will be counted.

When the pandemic pushed unprecedented numbers of voters to vote by mail, it took some states several days to do that work, which extended past Election Day. As 2024 approaches, lawmakers in several of these swing states — at the request of election officials — are allowing more preprocessing.

Michigan is moving from an extremely limited 10-hour preprocessing window in 2020, which many election officials were unable to take advantage of because the approval came only a month before the electionsmore than a week away in 2024. Wisconsin could soon plan a day of pre-treatment — less than many election officials had asked for, but it’s still something they consider much better than nothing.

“The early voting option in our state, along with preprocessing and other associated elements, will ultimately help us deliver unofficial election results more smoothly and efficiently after the polls close.” , Benson said.

Election officials in battleground states have been talking about counting ballots, she said, “as we prepare for close elections in each of our states next November and the challenges post- “Electoral issues and disinformation will flourish as a result.”

Some states have also passed laws that would give the public a better idea of how many votes remain to be counted, removing a level of uncertainty that could help media decision-making offices as they seek to declare winners.

Georgia, for example, now requires counties to report by midnight on Election Day how many votes they have left to count, as does Pennsylvania.

“I think you’re going to see, as we did for the 2022 cycle, that people will be declared winners around 9:30 or 10 p.m. at night,” said Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican. “The closer races lasted a little longer. But it was precisely because of the very, very close races that we were unable to make a decision that evening.

Some battleground states have not made significant changes.

Much to the frustration of Pennsylvania election officials, state lawmakers did not allow mail-in ballots to be preprocessed, preventing Pennsylvania officials from touching them before voting opened. The issue has repeatedly fallen victim to partisan fighting within Pennsylvania state government.

“It’s certainly disappointing that the Legislature hasn’t been able to come together and provide at least a few days of pre-processing,” said Philadelphia Republican election official Seth Bluestein. This didn’t matter in recent low-turnout municipal elections. But, he added, “when we enter next year with higher turnout and potentially a narrow statewide margin, it will certainly be difficult to count all the ballots quickly “.

Pennsylvania, however, is a significant exception.

Rachel Orey, senior associate director of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Election Project, noted that 40 states and D.C. allow some level of preprocessing of mail-in ballots before Election Day — compared to just 27 states in 2020.

Election officials have long complained that election results were never official on election night. No state has completely counted all votes cast before midnight on Election Day — at a minimum, military and other overseas voters are given a grace period. And it is the media, not election officials, who declare winners early, with certification of actual election results occurring long after the public has left.

Nevada Secretary of State Cisco Aguilar, a Democrat, said focusing on certification is not a good way to think about it. “This is a problem for Nevada voters getting the information they expect to get,” he said. “Until we achieve perfection, we cannot use this argument.”

However, a very close contest could mean that the media does not have the statistical confidence to declare a winner. The Associated Press, for example, generally does not call an election if it falls within the margin of a recount.

And even having pretreatment periods is not a panacea.

It doesn’t help if a large number of ballots are cast on Election Day. And in some states, including Nevada, ballots are counted if they are postmarked by Election Day and arrive shortly thereafter. By definition, these last minute bulletins cannot be processed in advance.

Aguilar said his office is working to help local officials increase their capacity, particularly in Clark and Washoe counties, which together represent a large majority of the state’s votes. “It’s about making sure we have enough talent to manage the process. It’s about making sure we have enough machinery and enough space,” he said. “Should we increase the number of polling place collections to be able to collect ballots before the end of Election Day?

Perhaps one of the biggest differences from 2020 is that election officials in many states expect far fewer people to vote by mail in 2024 and are instead opting for a return to Election Day or a in-person early voting. In the 2022 midterm elections, more voters cast absentee ballots than in 2018, but it was significantly less than in 2020.

“Sixty-five percent of voters vote in advance. And then we have the other 30 percent who will vote on Election Day,” Raffensperger said. “Voters can make that choice, which gives them confidence in the process. But by doing that, we’ll have a very quick total for all the early votes.