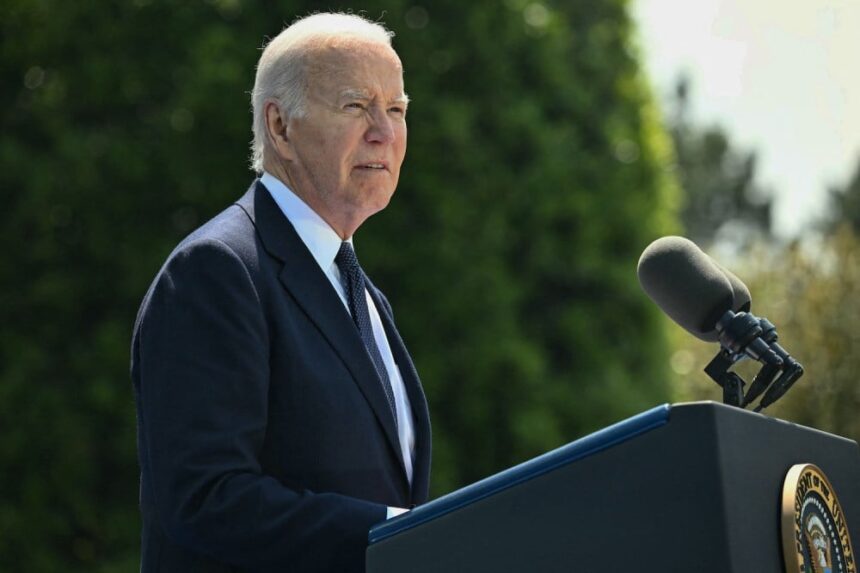

US President Joe Biden locations his re-election bid as a defense of American democracy itself. It’s a clever strategy because his opponent displays an awkward affection for autocrats. However, with a speech in France this week to commemorate the anniversary of D-Day and “the importance of defending freedom and democracy,” his team could signal a strategy of presenting Biden as a bulwark of democracy not only in his country, but also across the world – especially as wars in Ukraine and the Middle East are likely grind until election day. An institute for global affairs investigation that my colleagues and I published this week strongly suggests that this may be a strategic error.

US President Joe Biden locations his re-election bid as a defense of American democracy itself. It’s a clever strategy because his opponent displays an awkward affection for autocrats. However, with a speech in France this week to commemorate the anniversary of D-Day and “the importance of defending freedom and democracy,” his team could signal a strategy of presenting Biden as a bulwark of democracy not only in his country, but also across the world – especially as wars in Ukraine and the Middle East are likely grind until election day. An institute for global affairs investigation that my colleagues and I published this week strongly suggests that this may be a strategic error.

During the State of the Union address in March, Biden warned that American democracy is more “under attack” than it has ever been since the Civil War. This reality alone should be moving enough. But he diluted the message by quickly linking it to attacks on democracy abroad by referencing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, thereby turning a powerful policy proposition into one less important to American voters.

The Biden administration’s rhetoric has upped the ante. In his telling, the war in Ukraine is not simply a regional conflict with very specific historical origins, but is part of a global existential conflict. battle between democracy and autocracy. This ideological framework has troubled some members of Biden’s national security team, who see Ukraine’s fight as a simple defense of its sovereignty and independence rather than a noble fight against autocracy on behalf of the world free.

When I mentioned that Secretary of State Antony Blinken must have known that this framing distorted the essential dynamics of the conflict, a senior White House official confided, on condition of anonymity, that it came directly from the Oval Office.

Why might Biden lead an international crusade for democracy when preserving it at home seems urgent enough? In the 20 years since veteran John Kerry lost the presidential election to rebel George W. Bush, chastened Democrats have made a concerted effort to reassert themselves as a hard-line party. with regard to defense. I witnessed this conversion up close shortly after working on the Kerry campaign. From the ashes of the 2004 defeat was born organizations dedicated to strengthening the good faith of democratic national security. But decades of Democratic hawks and neocon Republicans trying to outdo each other have left the American public war-weary, amid a dismal record of fruitless and counterproductive conflicts.

While many American voters certainly want a strong national defense and have always been quick to support measures to defeat direct threats, such as the Soviet Union or Al-Qaeda, Americans have never wanted their country to act as the sword and shield of democracy on a global scale. . In April, when my colleagues and I at the Institute for Global Affairs surveyed voting-age Americans about what the United States should prioritize in Ukraine, half as many wanted deter autocracies from invading democracies than those who wanted to avoid taking risks. a confrontation between nuclear powers. Similarly, twice as many respondents wanted Washington to prioritize avoiding an escalation into a broader regional war than those who wanted to prioritize restoring Ukraine’s pre-invasion borders.

At a time when Ukrainian morale and momentum are declining subsidence and Russian President Vladimir Putin apparently looking for a ceasefire and the resumption of peace talks, we have noted broad support in the United States for NATO countries demanding a negotiated settlement. Lest this be seen as mere American provincialism or apathy toward foreign affairs, it’s worth noting that we also surveyed residents of the three largest NATO economies besides the United States: Germany, the United Kingdom and France. A majority of respondents from these European publics also want to push for a negotiated settlement.

There are significant differences between the reasoning of American and European respondents: for example, more Americans are concerned about Ukraine’s loss of influence, while more Europeans think that Ukraine is losing influence. The West does not have the industrial capacity to protect itself and Ukraine. But the idea that the war is Ukraine’s fight, and therefore we should refrain from trying to influence it – a recurring idea subject of discussion of the Biden administration – won the agreement of fewer than one in five people on either side of the Atlantic.

Biden could convincingly argue that another Donald Trump presidency would threaten America’s long-standing alliances. Indeed, Trump has bizarrely encouraged Russia to do “whatever it wants” to NATO allies that are failing to meet their spending commitments.

But here too, caution is required. A large majority of respondents in the United States – and in the three NATO member countries we surveyed – said want Europe to be primarily responsible for his own defense. In fact, nearly three times as many Europeans say they seek a neutral relationship with the United States as those who want Washington to be primarily responsible for Europe’s defense. The lofty paeans to a United States indispensable to European security may have resonated throughout Biden’s political career, especially during the Cold War, but they fail today.

The war in Gaza also does not present many opportunities for Biden to present himself as a champion of democracy and an international order based on liberal norms. Israel’s conduct in its war against Hamas has led the International Court of Justice to warn of acts of genocide and order a stop of sound military operation in Rafah “immediately.”

Our poll found that 42 percent of Americans thought Israel should agree to a lasting ceasefire, far more than the 28 percent who said the West should support Israel’s defense. Meanwhile, a new survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in March and April found that even about three-quarters of Israelis wanted the United States to play a major diplomatic role in ending its war, and more believe Biden overly favors them than to think that he excessively favors the Palestinians.

Biden is certainly right to be concerned about the state of democracy around the world. Authoritarians persist in pursuing odious ends. The democratic backsliding and populist reaction against globalization affects many countries other than its own. But Americans simply don’t show much enthusiasm for a warrior president focused on defending democracy in Ukraine, Israel, or probably any other faraway country. If Biden can avoid the temptation to be one, he will be better able to neutralize the main threat to democracy in the United States: the one that joins him on the November ballot.